Spring Skies, a Solar Eclipse, and the Shadow of a Black Hole – Star Trails: A Weekly Astronomy Podcast

Episode 57

In this episode we explore the night sky from March 23-29, highlighting the waning crescent moon, a lineup of bright planets, and an upcoming partial solar eclipse—though not everyone will get a chance to see it.

This week, we also take a look at two constellations that mark the arrival of spring: Virgo and Cancer. From galaxy clusters in Virgo to the Beehive Cluster in Cancer, there’s plenty to discover with just a small telescope or binoculars.

Also, the biggest mystery of the cosmos takes center stage as we revisit one of the greatest achievements in modern astronomy—the first-ever image of a black hole. We’ll break down how astronomers used the entire Earth as a telescope to photograph the supermassive black hole at the heart of M87.

Transcript

[MUSIC]

Howdy stargazers and welcome to this episode of Star Trails. I’m Drew, and I’ll be your guide to the night sky for the week starting March 23rd through the 29th.

This week, we have a waning crescent moon, a lineup of bright planets, and an upcoming partial solar eclipse—though it won’t be visible from everywhere. We’ll tour through the spring constellations Virgo and Cancer, and we’ll examine how the first image of a black hole was created using a planet-sized telescope. So, grab a comfortable spot under the night sky, and let’s get started!

The moon starts this week in its waning crescent phase, meaning it’s getting smaller each night as it approaches the New Moon on March 29th. If you’re up before dawn, look for a thin sliver of moonlight in the eastern sky, especially earlier in the week.

With less moonlight washing out the sky, this is the perfect time to catch a glimpse of faint galaxies, nebulae, and star clusters. On March 29th, the New Moon means the moon will be completely invisible, offering an ideal night for stargazing!

Venus, now the “Morning Star,” is beginning to rise in the predawn eastern sky. If you’re an early riser, watch for Venus low on the horizon just before sunrise. Mars will be visible after sunset, hanging in the sky for more than nine hours into the late evening. With its reddish hue, it’s easy to spot in Gemini, near the twin stars Castor and Pollux.

Jupiter is still one of the brightest objects in the night sky, best seen just after sunset. It’s fairly high in the western sky just after sunset, hanging out in Taurus.

[TRANSITION FX]

As we look towards April, let’s take a moment to spotlight two constellations that signal the arrival of spring: Virgo and Cancer. Both have unique characteristics and house some stunning deep-sky objects that are worth exploring.

Virgo, The Maiden of the Skies, is one of the largest constellations and plays a major role in spring stargazing. It is also one of the 12 zodiac constellations and is often associated with harvest and fertility myths across different cultures.Virgo is best identified by its brightest star, Spica, a brilliant blue-white star that sits about 260 light-years away from Earth. Spica is a binary star system—two stars locked in a close dance around each other.

To locate Virgo, draw an imaginary arc from the handle of the Big Dipper to Arcturus in Boötes, and then extend it downward to Spica. This is the famous stargazing guide: “Arc to Arcturus, then speed on to Spica!”

Virgo is home to some of the richest galaxy fields in the night sky. Some of the most famous objects include:

The Virgo Cluster of Galaxies: This enormous collection of galaxies is about 50 million light-years away and can be found between Leo and Virgo. The cluster contains more than 1,300 spiral, elliptical, and irregular galaxies, many of which can be seen with a medium-sized telescope.

Messier 87 is one of the brightest galaxies in the Virgo Cluster. M87 is a giant elliptical galaxy and is famous for being the home of the first black hole ever imaged in 2019! We’ll talk about how that image was created in the second half of the show. If you have a telescope, you might just catch a glimpse of its faint, glowing core.

The Sombrero Galaxy, M104: This edge-on spiral galaxy looks like a sombrero hat, with a bright central bulge and a dust lane cutting across it. Located just outside the Virgo Cluster, M104 is 28 million light-years away and shines at a magnitude of +8, making it a great target for small telescopes.

Now, let’s shift to a constellation that doesn’t always get as much love—Cancer, the Crab. Cancer is one of the faintest zodiac constellations, but it holds some amazing deep-sky objects.

Cancer sits between Gemini and Leo. Since it lacks bright stars, the best way to locate it is by looking between the bright twin stars of Castor & Pollux and the star Regulus in Leo. Once you find this faint region, you’re looking at Cancer!

Cancer is home to one of the best open star clusters in the entire night sky, the Beehive Cluster, M44. This swarm of stars is one of the brightest and closest open star clusters to Earth—just 577 light-years away! It contains more than 1,000 stars, many of which are similar to our Sun, making it one of the most rewarding sights for backyard astronomers

In dark skies, it’s visible to the naked eye, appearing as a hazy patch. A pair of binoculars will reveal dozens of bright stars swarming together, just like bees in a hive!

Telescope owners may want to chase down M67, one of the oldest open clusters. Perhaps even more intriguing than the Beehive Cluster, M67 is estimated to be 4 billion years old—meaning some of its stars are nearly as old as our Sun! It contains around 500 stars and lies about 2,700 light-years away. Astronomers study it to understand how Sun-like stars evolve over time.

M67 is visible in binoculars, although a telescope will reveal more individual stars packed into its core.

[TRANSITION FX]

A partial sunrise solar eclipse is happening on March 29th! But sadly—it’s not visible for most of us here in the states.

A partial solar eclipse happens when the Moon passes between the Earth and the Sun, but they don’t align perfectly. This results in the Moon covering only a portion of the Sun’s disk, taking a characteristic “bite” out of the Sun.

In the northeastern United States and eastern Canada, the eclipse will be visible at sunrise. For example, in Hartford, Connecticut, the event starts around 6:38 AM EDT, reaches its maximum at 6:41 AM, and concludes by 7:07 AM. The best views in the U.S. will be in northeastern Maine, where up to 85% of the Sun will be obscured at sunrise.

The eclipse will be observable across much of Europe during the late morning. In London, approximately 30% of the Sun will be obscured, with the event occurring between 10 AM and noon GMT, peaking around 11 AM.

Since this isn’t a total eclipse, be sure to take precautions to view it. Use certified eclipse glasses or handheld solar viewers. Regular sunglasses or darkened glass do not provide adequate protection.

[TRANSITION FX]

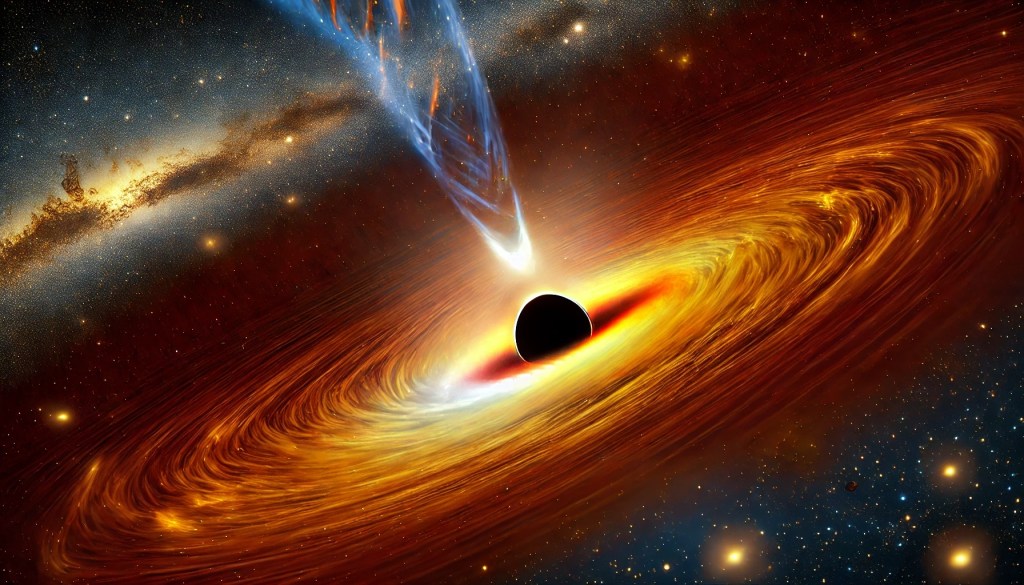

On April 10, 2019, history was made when scientists released the first-ever image of a black hole, located in the center of the galaxy M87 in the Virgo Cluster. This groundbreaking achievement was the result of an international collaboration known as the Event Horizon Telescope project, a network of radio telescopes around the world working together to capture an object that, by its very nature, is invisible.

A black hole is a region of space where gravity is so intense that nothing—not even light—can escape it. Black holes form when massive stars reach the end of their life cycles and collapse under their own gravity. This collapse can result in a stellar-mass black hole, typically a few times the mass of our Sun, or, over billions of years, grow into a supermassive black hole at the center of a galaxy.

Supermassive black holes, like the one in M87, are millions or even billions of times the mass of the Sun. Scientists believe they form over time, possibly from the merging of smaller black holes and the accumulation of vast amounts of matter. These cosmic giants exert tremendous gravitational influence, shaping the orbits of stars and affecting entire galaxies.

One of the defining features of a black hole is the event horizon—the boundary beyond which nothing can return. Any matter or light that crosses this threshold is permanently lost to the singularity, a point where gravity is thought to become infinitely strong. Surrounding the event horizon is an accretion disk, a swirling, superheated ring of gas and dust falling toward the black hole. This glowing material is what allows astronomers to detect and study black holes, even though the black holes themselves are invisible.

The black hole that was imaged lies at the heart of M87, a giant elliptical galaxy in the Virgo Cluster, about 55 million light-years away from Earth. This black hole is a monster, with a mass of 6.5 billion times that of our Sun!

It was chosen as the target of the Event Horizon Telescope project because it’s relatively close (cosmically speaking), making it one of the easiest supermassive black holes to observe. Also, it has an enormous event horizon, meaning it would cast a large shadow that could be detected.

It’s surrounded by a bright accretion disk, providing the perfect contrast to capture the black hole’s “silhouette.”

The Event Horizon Telescope isn’t a single telescope, but a network of eight radio telescopes positioned around the world—from Chile to Hawaii, the U.S., Spain, and Antarctica. By linking these telescopes together, astronomers effectively created a planet-sized telescope using a technique called very long baseline interferometry. This allowed them to achieve the resolution needed to image something as small as a doughnut on the Moon’s surface.

The final image, assembled from petabytes of data, revealed the now-famous “fiery ring”—a circular glow of superheated gas surrounding a dark central shadow, which is the event horizon of the black hole.

The image provided direct evidence that black holes exist and behave as predicted by Einstein’s relativity. It confirmed that black holes can be imaged and it gave scientists insight into how matter behaves in extreme gravitational environments.

This image was only the beginning. The EHT has since produced a similar image of Sagittarius A*, the black hole at the center of our Milky Way, and continues refining its methods to uncover even more secrets of the universe.

While you can’t see the black hole from your backyard, you can definitely see M87, and knowing that a supermassive black hole is right in the middle of it, is a powerful idea to ponder!

[MUSIC]

If you found this episode helpful, let me know, and feel free to send in your questions and observations. The easiest way to do that is by visiting our website, startrails.show. This is also a great way to share the show with friends. Until next time, keep looking up and exploring the night sky. Clear skies, everyone!

Support the Show

Connect with us on Mastodon @star_trails or on Bluesky @startrails.bsky.social

If you’re enjoying the show, consider sharing it with a friend! Want to help? Buy us a coffee!

Podcasting is better with RSS.com! If you’re planning to start your own podcast, use our RSS.com affiliate link for a discount, and to help support Star Trails.

Leave a comment