Cosmic Rebels & Celestial Farewells – Star Trails: A Weekly Astronomy Podcast

Episode 62

This week we say goodbye to Comet SWAN as it disintegrates on its first — and last — visit to the inner solar system. With a New Moon offering ideal stargazing conditions, we turn our attention to the Summer Triangle, Venus and Saturn’s pre-dawn pairing, and Mars dancing near the Beehive Cluster.

In the second half, we spotlight the galaxy’s rebellious loners: Runaway stars. From the aftermath of supernovas to gravitational billiards near black holes, discover how some stars break free and speed through space at hundreds of kilometers per second. We’ll explore how they’re formed, how we find them, and why stars like HV 2112 and Zeta Ophiuchi continue to baffle and amaze astronomers.

Links

Transcript

[MUSIC]

Howdy stargazers and welcome to this episode of Star Trails. I’m Drew, and I’ll be your guide to the night sky for the week starting April 27th through May 3rd.

This week a New Moon promises darker skies, the Summer Triangle points the way to warmer days, and did you know stars sometimes run away from home. More on that weird phenomenon later. So, grab a comfortable spot under the night sky and let’s get started.

[MUSIC FADES]

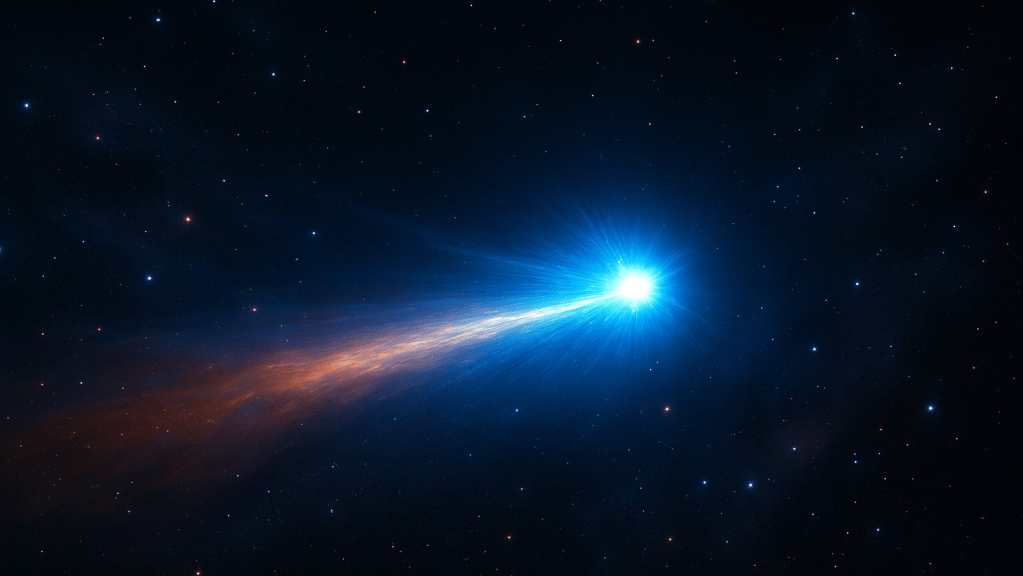

Before we dive into this week’s highlights, a quick update about Comet C/2025 F2, also known as Comet SWAN. Last week, we talked about this comet potentially putting on a good show. Unfortunately, after the episode aired, astronomers reported that Comet SWAN began to disintegrate as it approached the Sun. This was likely due to the comet’s first venture into the inner solar system, where intense heat and gravitational forces broke its nucleus apart.

Interestly, a cloud of debris remained visible shortly after the breakup, but of course that’s fading fast. With that, we say goodbye to Comet SWAN. As of now, I don’t know of any other comets expected to make a splash this year. But you never know what might turn up. Keep in mind, we didn’t know SWAN was out there until about a month ago.

Closer to home, tonight marks the New Moon, meaning our skies will be beautifully dark and ideal for observing those fainter celestial objects, such as galaxies and nebula. As the week moves on, the Moon will gradually brighten into a delicate Waxing Crescent, reaching about 40% illumination by Saturday. This crescent will be visible shortly after sunset.

Speaking of bright sights, Venus reaches its greatest illuminated extent this week, blazing in the pre-dawn eastern sky. Venus will be exceptionally bright, making it hard to miss if you’re an early riser. On the very next morning, April 28, Saturn joins Venus, creating a lovely close pairing just under four degrees apart.

Mars continues its journey across the sky, now moving closer to the famous Beehive Cluster, or M44. Binoculars will show you Mars as it passes near this sparkling open star cluster in the constellation Cancer.

Jupiter remains a prominent evening planet, easy to spot after sunset toward the western sky. With a telescope, you’ll easily spot its Galilean moons dancing around it. For an added challenge, look for a transit of one of the moons and see if you can spot its shadow moving across Jupiter. You can use an online tool such as Sky & Telescope’s Jupiter’s Moons calculator (https://skyandtelescope.org/observing/jupiters-moons-javascript-utility) to determine when events like these happen.

While the Lyrid meteor shower peaked last week, keep an eye out—you might still catch some lingering meteors streaking across the sky, especially in the early part of the week. Additionally, the Eta Aquarid meteor shower is starting to ramp up, and although it peaks next week, you might see a few early meteors during the pre-dawn hours, particularly from darker locations.

Now, shifting our gaze to constellations, let’s explore the emerging Summer Triangle. This well-known trio of bright stars, Vega, Deneb, and Altair, begins to rise in the east around 10 PM, signaling the approach of warmer months.

Vega, in the small yet vibrant constellation Lyra, is the brightest of the three and has been central to myths connected to music and poetry. Lyra is home to the Ring Nebula (M57), a beautiful planetary nebula visible as a tiny smoke ring in small telescopes. Also noteworthy is Epsilon Lyrae, famously known as the “Double Double,” where careful observation reveals not just one, but two pairs of stars orbiting closely together.

The constellation Cygnus, the Swan, is marked by Deneb, one of the farthest bright stars visible without optical aid. Within Cygnus, you’ll find the impressive North America Nebula (NGC 7000), named for its striking resemblance to our continent, and the elegant Veil Nebula, the ghostly remnants of a supernova explosion. Don’t miss Albireo at the Swan’s head—a double star pairing with golden and blue hues.

[TRANSITION FX]

Have you ever heard of a runaway star? These cosmic rebels have broken free from their stellar neighborhoods and are now barreling through the galaxy at astonishing speeds—sometimes fast enough to escape the Milky Way altogether.

In simple terms, a runaway star is a star moving significantly faster than the stars around it, often hundreds of kilometers per second. These stars don’t just meander along with the gentle galactic rotation like most of their neighbors, they’re hurtling through space like they’ve got somewhere to be. Many are on paths that suggest they’ve been violently ejected from their original homes, flung out into the galaxy by powerful forces.

There are two main mechanisms thought to be responsible for this high-velocity behavior:

One theory involves supernova explosions in binary systems. In this scenario, two stars orbit one another in a binary system. When the more massive star reaches the end of its life and explodes in a supernova, the sudden release of mass can destabilize the system. The surviving star might be sent flying off into space at tremendous speeds.

The violence of a supernova is enough to break the gravitational bond, and the energy imparted can slingshot the remaining star into a lonely galactic journey.

Another theory points to gravitational interactions in star clusters. In dense star clusters, particularly those near the galactic center or in globular clusters, three- or four-body interactions can fling a star out at high velocity. This is a bit like a cosmic game of pool; one star gets knocked out of the cluster owing to complex gravitational interactions with multiple other stars or a massive black hole.

One of the most exciting subsets of runaway stars are hypervelocity stars. These are moving so fast they are on escape trajectories out of the galaxy entirely. These were first predicted theoretically in the 1980s and confirmed observationally in the 2000s. They often originate from interactions with the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. In a tight dance between stars and the black hole’s immense gravity, one member of a binary pair can be captured while the other is flung away at speeds exceeding a million miles per hour.

Among these standout objects is HV 2112 (I don’t know if that’s a RUSH reference, but it would be appropriate!) 2112 is a curious and controversial star located in the Small Magellanic Cloud. While not technically a hypervelocity star, it’s earned attention for its bizarre chemical makeup and potential status as a Thorne–Żytkow object — a theoretical hybrid of a red supergiant and a neutron star.

In terms of observable characteristics, runaway stars don’t look all that different from other stars, at least not through traditional telescopes. They may appear as hot blue O- or B-type stars—large, young, and luminous. In other cases, they might be older or redder stars. The key difference is not what they look like but how they move. Their proper motion — that’s their movement across the sky relative to more distant stars — can be measured over time with the help of space telescopes and long-term sky surveys.

Modern surveys like Gaia have been instrumental in identifying runaway stars. Gaia precisely measures the positions, motions, and distances of over a billion stars in the Milky Way. By plotting the motion vectors of these stars, astronomers can spot the few that are zooming through the galaxy in ways that don’t conform to the general structure and rotation of the Milky Way.

As for backyard astronomy, runaway stars aren’t something we normally seek out. They don’t emit unique light or have any distinguishing visual characteristics.

But some of the most famous runaway stars, like Zeta Ophiuchi, are visible with amateur telescopes or even binoculars. Zeta Ophiuchi is a massive, hot blue star that’s plowing through space and creating a visible bow shock, that’s an arc-shaped wave in the interstellar medium much like a boat cutting through water. Infrared images reveal this shockwave in beautiful detail.

So next time you’re under a clear sky, remember: somewhere out there, maybe even above your head, a star is fleeing a supernova, escaping a black hole, or wandering alone from a starry birthplace it no longer calls home.

[MUSIC]

If you found this episode helpful, let me know, and feel free to send in your questions and observations. The easiest way to do that is by visiting our website, startrails.show. This is also a great way to share the show with friends. Until next time, keep looking up and exploring the night sky. Clear skies, everyone!

[MUSIC FADES OUT]

Support the Show

Connect with us on Mastodon @star_trails or on Bluesky @startrails.bsky.social

If you’re enjoying the show, consider sharing it with a friend! Want to help? Buy us a coffee!

Podcasting is better with RSS.com! If you’re planning to start your own podcast, use our RSS.com affiliate link for a discount, and to help support Star Trails.

Leave a comment