Four Worlds, One Sun; Plus, a Total Lunar Eclipse – Star Trails: A Weekly Astronomy Podcast

Episode 78

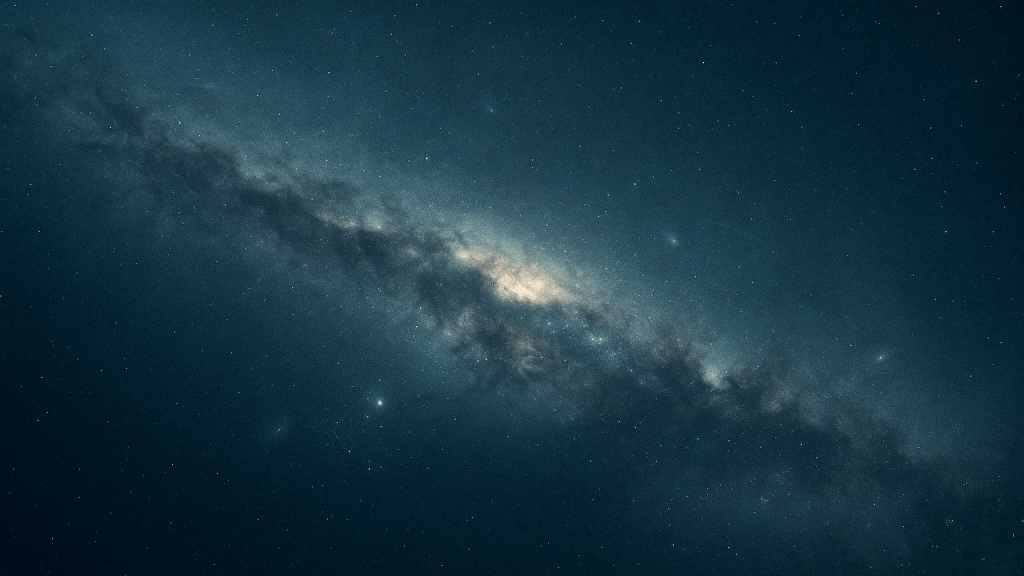

Under a rare seasonal Black Moon, this week’s sky rewards early risers and deep-sky wanderers alike. We start with a whisper-thin crescent slipping closer to the Sun each morning, then pivot to a dawn showcase where Mercury reaches greatest elongation while Venus and Jupiter stack higher above the horizon. On Tuesday and Wednesday a paper-thin crescent Moon joins the lineup—a perfect wide-field photo op—while evenings bring Saturn rising into prime viewing on its road to September opposition. With moonlight out of the way, scan the Milky Way for under-sung binocular treats: Delphinus the Dolphin, M11 (Wild Duck Cluster) in Scutum, and the Coathanger asterism in Vulpecula. You may even catch a few Perseid stragglers in the pre-dawn dark.

In the second half, we widen the frame to reveal the Milky Way’s “hidden companions”—dozens, maybe hundreds, of ultra-faint dwarf galaxies quietly orbiting our own. We unpack why they’re so hard to see (surface brightness, not just brightness), how modern surveys like SDSS and DES ferret them out, and why they matter for big questions about dark matter, galaxy growth, and the “missing satellites” problem.

Links

Transcript

[MUSIC]

Howdy stargazers, and welcome to Star Trails. I’m Drew, and I’ll be your guide to the night sky for the week of Sunday, August 17th to the 23rd. This is a week designed for patient eyes and early alarms. We have slim crescents at dawn, a lovely planetary trio before sunrise, and the darkest weekend of the month for deep-sky hunting.

Then, in the second half of the show, we’ll widen the frame and talk about the Milky Way’s “hidden companions,” dozens of ghostly little galaxies that have been circling us all along, almost invisibly, and how they’re reshaping our sense of home in the universe.

[MUSIC FADES]

Let’s begin with the Moon. Right now it’s a delicate waning crescent hugging the pre-dawn eastern horizon. Each morning it slims further and slides closer to the Sun’s glare. By Friday it’s little more than a silver thread in brightening twilight.

The New Moon arrives early Saturday morning. This isn’t just any new moon; it’s what astronomers and calendar-keepers call a seasonal Black Moon, the rare case when one astronomical season contains four new moons instead of the usual three, and this is the third of the four.

It’s mostly a calendar quirk, but practically speaking, it means Friday and Saturday nights bring the darkest skies of the month. If you’ve been waiting for the Milky Way to leap out of the sky, or you want to take a crack at the Andromeda Galaxy with the naked eye from a truly dark site, this is your moment.

The pre-dawn sky is where the week’s best show plays out. On Tuesday, August nineteenth, Mercury reaches its greatest western elongation for this apparition. About 30 to 40 minutes before sunrise, scan very low in the east-northeast. Mercury will be bright for a small planet, but still close to the horizon; a pair of binoculars will punch through the haze and help you spot it.

Now look higher up that same stretch of sky and you will find Venus and Jupiter, still sharing the stage after last week’s conjunction. Venus blazes lower; Jupiter shines above it. On Tuesday and Wednesday, a paper-thin crescent Moon joins them in the morning twilight, turning the scene into a gorgeous quartet: Mercury near the horizon, Venus brighter above it, Jupiter higher still, and the Moon as a delicate accent.

Evening planets are quieter but worth a look. Mars clings to the low western horizon right after sunset. It is faint, small, and sets quickly, so you will need an unobstructed view and a bit of luck with atmospheric clarity.

By late evening, Saturn is the reward, rising in the east-southeast and climbing higher night by night as it heads toward opposition on September 21st. Even a small telescope will show its rings and, with patient viewing, the tiny star-like point of Titan nearby. If you have not seen Saturn this year, mark it down; late August through September is prime time.

The Perseid meteor shower peaked last week, but it doesn’t switch off like a faucet. Perseids linger through late August, and a few bright stragglers are very possible in the pre-dawn hours, especially now that moonlight will not be washing the sky. If you’re up early for the planet lineup anyway, give yourself fifteen or twenty minutes just to scan the sky. Face generally northeast, but don;t fixate on the radiant; meteors can streak across any part of the sky, and you will spot more by letting your peripheral vision do the work.

If you want targets for the dark evenings later this week, let me recommend three summer gems that don’t get a lot of hype. The first is Delphinus, the Dolphin, a little diamond-and-tail asterism just east of Altair that resembles a leaping dolphin. Second is Scutum, the Shield, small and unassuming but home to M11, the Wild Duck Cluster. Through binoculars or a small scope it looks like a burst of stardust against the Milky Way, dense, rich, and full of texture.

The third is Vulpecula, the Fox, which hides the famous Coathanger asterism, six stars in a bar with four forming the hook. Sweep slowly between Altair and Vega, and once you see the Coathanger you will never unsee it. Under this weekend’s moonless sky, all three reward a patient scan.

In recent episodes we’ve journeyed out to the darkness at the edge of our solar system to explore objects in the Kuiper Belt and beyond. But what will we find when we venture out to the edge of our galaxy? That’s coming up after the break. Stay with us.

[MUSIC]

Welcome back!

Today we’re talking about the Milky Way’s “hidden companions.” When you stand under a truly dark sky this weekend and the Milky Way glows like a river of light, it is tempting to think we know this city of stars well. We’ve mapped its spiral arms, traced its dusty lanes, and even weighed the giant black hole at its center.

But there is a surprise waiting just beyond the obvious: our galaxy is surrounded by dozens—maybe hundreds—of ghostly little galaxies, quietly orbiting the Milky Way like dim satellites. Some are so faint that until recent years we didn’t know they existed.

Astronomers call them dwarf galaxies, and the faintest among them are known as ultra-faint dwarfs. They are small collections of stars and dark matter bound together by gravity. A typical ultra-faint dwarf may contain only a few thousand stars spread over hundreds of light-years. By comparison, the Milky Way holds hundreds of billions of stars. If we think of the Milky Way as a bright metropolis, these dwarfs are outlying towns, sparsely populated, dimly lit, and far from the bustle of the core.

Why did we miss them for so long? The answer is partly about surface brightness. It’s not just how much light an object emits, but how spread out that light is in the sky. Many of these dwarfs are so diffuse that their stars melt into the background. They don’t “pop” the way a bright cluster or nebula does.

The breakthrough came with enormous digital sky surveys and sophisticated search techniques. The Sloan Digital Sky Survey was a pioneer here, and the Dark Energy Survey dramatically expanded the census, revealing a host of ultra-faint candidates by looking for tiny overdensities. These are little knots where there are just a few more stars than you would expect by chance. Follow-up spectroscopy then distinguishes true galaxies from star clusters by measuring how the stars move.

Galaxies show the signature of dark matter; clusters do not. And the floodgates are still opening. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory, coming fully online soon, will map the southern sky over and over for a decade, essentially making a time-lapse movie of the universe. It is expected to add dozens, maybe hundreds more of these ghostly satellites to the map.

These little galaxies matter in big ways. First, they are dark-matter laboratories. Dwarfs are often dominated by dark matter, so by measuring the motions of their stars astronomers can probe how dark matter clusters on small scales.

Second, they are crucial clues to galaxy evolution. Massive galaxies like the Milky Way likely grew by merging with smaller ones, and many dwarfs are survivors or new arrivals in that ongoing story. Some are actively being torn apart, leaving long streams of stars wrapped around our galaxy like faint ribbons.

Third, they speak directly to the “missing satellites problem.” Computer simulations predict that a Milky Way-sized galaxy should have hundreds of tiny companions. We have found a few dozen so far. Either most of the rest are simply too faint to notice until recently and we are just now finding them, or our models need fine-tuning. Either way, the science gets sharper.

A few examples make this concrete. The Sagittarius Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxy is so close to us that our gravity is shredding it. Its stars have been pulled into great arcs, tidal streams, that circle the sky and are visible in deep survey data.

The Canis Major Dwarf Galaxy, discovered in 2003, may be the closest galaxy to our own, hiding behind the thick dust and starfields of the Milky Way’s disk only 25,000 light-years from us. And Segue 1, an ultra-faint dwarf discovered in Sloan data, might be the dimmest known galaxy, with only a few hundred visible stars. On an image, it looks like nothing more than a slightly suspicious smudge, yet its stars’ motions betray a deep well of dark matter. These aren’t showpieces at the eyepiece, but they’re goldmines for understanding how galaxies, including ours, came to be.

If you live or travel in the Southern Hemisphere, you can see two of the Milky Way’s brighter companions with your unaided eyes: the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, which look like detached pieces of the Milky Way itself floating off the side of the sky.

From northern latitudes, you can make a powerful connection by turning binoculars or a small scope toward the Andromeda Galaxy, M31. It’s not a satellite of the Milky Way, we and Andromeda are the two big cities in our Local Group. But thinking of us as Andromeda’s companion gives a helpful sense of scale and relationship. There is also a delightful binocular tie-in you can do from anywhere in the Northern Hemisphere: look toward the rich starfields of Sagittarius and find the globular cluster M54. This cluster is actually embedded in the Sagittarius Dwarf Galaxy. When you gaze at M54, you are peering into another galaxy’s star system!

You can also explore these faint satellites from the couch. The Sloan Digital Sky Survey’s online “Navigate” tools let you type in targets like “Segue 1” or “Canis Major Dwarf” and zoom into the exact patches of sky where they hide.

The Dark Energy Survey has public image galleries that show these ultra-faint dwarfs against deep starfields, and they are striking once you know what you are looking at. If you want a three-dimensional feel for the neighborhood, free software like Gaia Sky can let you “fly” around a model of the Milky Way and see where the known satellites live in our halo. I will drop pointers to all of these in the show notes.

There is a poetic link between this week’s seasonal Black Moon and these hidden galaxies. The Black Moon hides in the Sun’s glare, invisible not because it is absent, but because of where and when we are looking. The dwarf galaxies hide in the Milky Way’s own glare, invisible to our eyes until we gather enough light and apply enough patience. In both cases, the sky is reminding us that the obvious story is rarely the whole story. A darker sky reveals more. A deeper look reveals the rest.

Our galaxy is not an island alone in the dark. It’s part of a quiet archipelago of companions, faint and fragile, sharing our long orbit through the universe.

[MUSIC]

If the stars spoke to you this week, or if a question’s been on your mind, I’d love to hear it. Visit our website, startrails.show, where you can contact me and explore past episodes. Be sure to follow us on Bluesky, and YouTube — links are in the show notes. Until we meet again beneath the stars… Clear skies everyone!

[MUSIC FADES OUT]

Support the Show

Connect with us on Bluesky @startrails.bsky.social

If you’re enjoying the show, consider sharing it with a friend! Want to help? Buy us a coffee!

Podcasting is better with RSS.com! If you’re planning to start your own podcast, use our RSS.com affiliate link for a discount, and to help support Star Trails.

Leave a comment