A Dark Sky for Us, and a New Moon for Uranus – Star Trails: A Weekly Astronomy Podcast

Episode 79

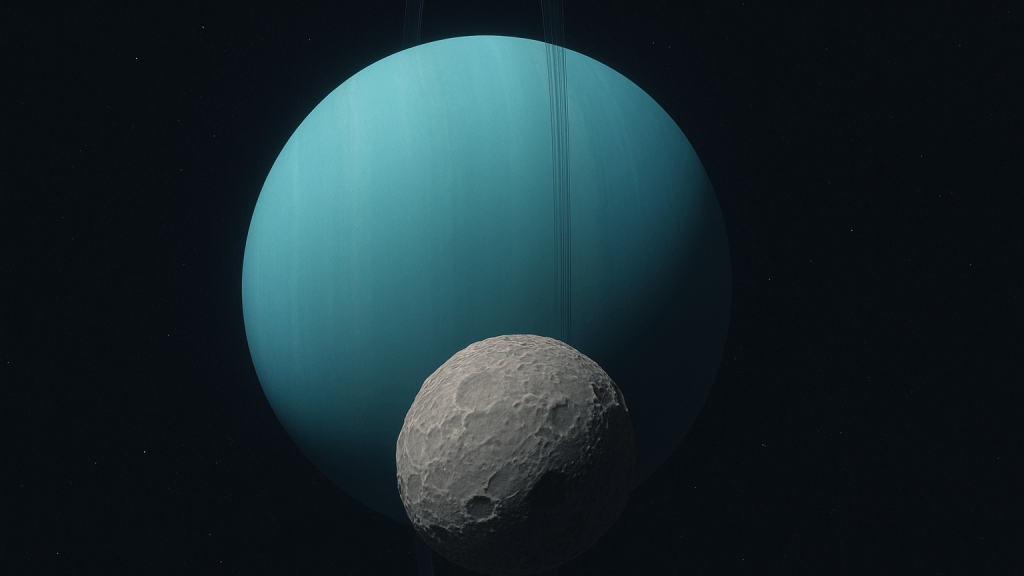

This week we head outward to the seventh planet, where the James Webb Space Telescope has revealed a brand-new moonlet orbiting Uranus. Barely six miles across, this tiny world is so small you could, in theory, walk around it in a single day. But is “walking” even possible when the surface gravity is only a whisper? We run the numbers and explore what it would feel like to live in such a micro-gravity landscape, where a careless jump could fling you into orbit.

Back under Earth’s skies, the nights begin in darkness. The week opens with a fresh New Moon, offering deep-sky windows before the crescent brightens. Saturn dominates the evening hours, Venus and Jupiter rule the dawn, and the Aurigids meteor shower brings a chance of surprise streaks before sunrise. We’ll also shine a light on three quieter constellations — Lacerta the Lizard, Aquarius the Water-Bearer, and Capricornus the Sea Goat — exploring the lore behind their faint patterns and the clusters, doubles, and globulars tucked among their stars.

From new moons both near and far, to the myths written across our own skies, this is a week for patient eyes, and a reminder of how scale and story intertwine in the universe.

Transcript

[MUSIC]

Howdy stargazers, and welcome to Star Trails. I’m Drew, and I’ll be your guide to the night sky for the week of Sunday, August 24th to the 30th.

This is a week that begins in darkness and ends with a silver lantern in the sky thanks to a waxing Moon. We’ll take a look at what else is up this week, and in the second half of the show, we journey out to Uranus, where a tiny new moon has just been discovered. More importantly, we wonder, what would it be like to walk around this tiny moon?

Whether you’re tuning in from the backyard, the balcony, or just your imagination, I’m glad you’re here. So, find a cozy spot, let your eyes adjust, and let’s see what the sky holds for us this week.

[MUSIC FADES]

The New Moon slipped past us on August 23, which means the first half of this week belongs to deep-sky hunters: galaxies, clusters, and nebulae without the lunar washout. But each evening the waxing crescent grows larger, rising higher in the west, until it becomes a bright beacon by Saturday night.

Try for the razor-thin crescent earlier in the week low in the west 20–45 minutes after sunset. By the week’s end the crescent is high enough to sketch shadows along the terminator when viewed with binoculars.

Saturn is the planetary star of the show this week. It lifts itself into the southeastern sky by mid-evening, its rings tilted just enough to remind us why Galileo once called them “ears.” A small telescope will reveal Titan as a tiny golden companion, and with larger optics you’ll spot multiple moons strung like faint pearls nearby.

Look east before dawn and you’ll find a brighter spectacle: Venus blazing like a spotlight, with Jupiter tagging along. They’ve been in conjunction recently, but even as they drift apart they still share binocular fields like two bright exclamation points in the morning twilight.

In the evening, Mars is hanging on low in the western twilight for about 45 to 60 minutes after sunset. It’s small and faint now, so we can treat it as a “goodbye glance” object this week.

Uranus rises around midnight, high before dawn in Taurus, drifting beneath the Pleiades this month, which makes it an easy star-hop target for 50–70mm binoculars under dark skies. Telescopes will reveal a tiny greenish disk.

Another meteor shower, the Aurigids, arrives this week, active from August 28 into early September. They’re usually modest, maybe ten streaks per hour at their best, but they’re quirky: the shower is known for sharp, unpredictable bursts. Their radiant lies in Auriga, climbing high before dawn, so the best time to watch is the final hours of darkness on Friday and Saturday morning. With only a slim crescent Moon, the sky is yours.

Now, let’s wander away from the Summer Triangle and dip into some lesser-traveled constellations you can see this month.

Lacerta the Lizard is a faint zigzag north of Cygnus, often overlooked. Its pattern is delicate, more a whisper than a shout, but sweep binoculars through and you’ll stumble across the open cluster NGC 7243, a loose scattering of stars that looks like a spilled box of jewels. Lacerta was only added to the official sky maps in the seventeenth century, a relative newcomer compared to the ancient Greek constellations.

Aquarius the Water-Bearer sits lower in the south, sprawling and hard to trace. In mythology, Aquarius pours the life-giving waters onto the Earth, but for observers it hides treasures of a different sort. Look for the globular cluster M2, a dense ball of stars about 37,000 light-years away, so bright that even small telescopes can resolve its grainy edges. The ancients saw Aquarius as a bringer of floods; astronomers see him as a keeper of starry vaults.

And then there’s Capricornus, the Sea Goat, straddling myth’s line between land and water. To the eye, it’s a pair of shallow triangles, almost like a sideways smile, low in the southern sky. In lore, the sea goat is tied to Pan, who leapt into the Nile to escape a monster, half-transformed into a fish.

Through the eyepiece, Capricornus is a playground of doubles and patterns, a geometry lesson written in stars. Scan slowly and you’ll find the planet Saturn parked here this season, the mythic goat sharing the stage with the lord of the rings.

These constellations may not command the same fame as Orion or Scorpius, but they reward patient eyes with quiet wonders.

You may have heard last week that a new moon has been discovered around Uranus, thanks to careful observations by the James Webb Space Telescope. This moon is only about 6 miles across, which made me wonder, is it possible to walk around it?

That’s coming up after the break. Stay with us.

[MUSIC]

Welcome back!

Astronomers have just added another body to Uranus’s family tree, a tiny moon, barely six miles across, whirling around the planet in less than ten hours per orbit. That bumps the official moon count for Uranus to 29. The little moon is currently known only by the placeholder name, S/2025 U1, but in keeping with tradition it’ll possibly be given a literary name, perhaps a character from Shakespeare or Alexander Pope.

The discovery was made with the James Webb Space Telescope with its jaw-dropping sensitivity and ability to view the near‑infrared. The new moon was spotted tucked within Uranus’s inner ring system, a region previously blind to Voyager 2 and Hubble. It’s kind of like spotting a pebble from 100 miles away.

Uranus already has a wonderfully eccentric entourage. There are the five big, rounded moons: Titania, Oberon, Ariel, Umbriel, and Miranda. These are strange places carved by canyons, cliffs, and perhaps hiding briny underground seas.

Then there’s a swarm of smaller inner moons that shepherd the planet’s delicate rings, and even more distant irregular satellites looping in eccentric orbits. Voyager 2 gave us our first and only close-up look back in 1986, discovering many of these worlds in a single flyby. Since then, telescopes have slowly filled in the roster.

But this new Webb find fascinates me because of its size. Normally when we’re talking about topics in astronomy, we’re measuring objects that are incomprehensible in size and scale. We often need to resort to exponents – 10 to some power – to describe distances, mass, and so on. For example, something gigantic, like the Milky Way galaxy, has a diameter around 10 to the 24th power in meters. That’s a 1, followed by 24 zeros. A nearly incomprehensible number.

But this newly discovered moon is really tiny in a way that makes it relatable. Some of you may know that I’m a walker. I try to get out and walk every day if possible, and in fact, one of these late night constitutionals planted the seed that resulted in this podcast.

At just ten kilometers across, this new moon is so small you could, in theory, walk all the way around it in a few hours. The idea intrigues me: a hiker’s circuit of an entire moon before lunch. The catch is, of course, gravity. Does an object this small produce enough gravity to keep an average human rooted on its surface.

So, we did the math, and the numbers are fascinating.

Let’s take a look at some figures, and just know, these are estimates:

The new moon is only about 10 km across, or roughly 6 miles. That means a radius of around 5,000 meters. If it’s made of dark, icy or rocky material like Uranus’s other inner moons, perhaps we can estimate the density around 1,200–1,800 kilograms per cubic meter. That means its surface gravity works out to roughly 0.00017–0.00026 g. That’s around 4,000–6,000 times weaker than Earth’s gravity.

On Earth, gravity is a firm tug. On S/2025 U1, it’s practically a whisper. Surface gravity would be about two-ten-thousandths of Earth’s. Put another way, if you weigh 180 pounds here, you’d “weigh” less than an ounce there. The escape velocity, that’s the speed you need to break free entirely, is only around 10 miles per hour. That’s a hard jog. Trip and shove off too forcefully, and you wouldn’t come down. You’d be in orbit for a moment, and likely drifting away into space.

So would walking even work? Well, not in the usual sense. Each step would act more like a little launch. You’d move in slow arcs, spending most of your time hovering above the surface before settling back down. To stay grounded, you’d need a tether, or something you can use to stay connected to the ground. Kind of like an ice climber using a pick on a slippery slope. With care, you could shuffle around, but it would feel like spelunking on a giant trampoline in slow motion.

Like the Earth’s Moon, the new Uranian moon is tidally locked, so it spins only once every time it orbits Uranus – about every 9.6 hours. So at the equator the ground slides under you at around 2 mph. That slightly reduces “effective gravity” and escape speed at the equator by 5–10%.

For comparison, Mars’s tiny moon Deimos, which is a bit larger than this object, has an escape speed around jogging pace; people often point out you could almost “jump to orbit.” This new moon is in that same ballpark.

There’s another factor at play here, and that’s the tidal forces of Uranus itself. If you’re trying to walk on the side of the moon facing Uranus, things get a little ticklish. You’d be even floatier, thanks to the massive influence of Uranus, which steals about a quarter of your already light weight. You won’t be yanked into space while you’re standing still, but a gentle hop could send you flying!

I hope you enjoyed this little thought experiment, or daydream really. There’s something beautifully peculiar about Uranus. It’s a sideways spinning planet hiding possible oceans, and ring-moon chaos that defies typical orbits. Now, Webb has shown us that Uranus contains even more secrets, and reminds us that the solar system is a lot less static than we sometimes think.

[MUSIC]

If the stars spoke to you this week, or if a question’s been on your mind, I’d love to hear it. Visit our website, startrails.show, where you can contact me and explore past episodes. Be sure to follow us on Bluesky, and YouTube — links are in the show notes. Until we meet again beneath the stars… Clear skies everyone!

[MUSIC FADES OUT]

Support the Show

Connect with us on Bluesky @startrails.bsky.social

If you’re enjoying the show, consider sharing it with a friend! Want to help? Buy us a coffee!

Podcasting is better with RSS.com! If you’re planning to start your own podcast, use our RSS.com affiliate link for a discount, and to help support Star Trails.

Leave a comment