The Myth of the Perfect Night – Star Trails: A Weekly Astronomy Podcast

Episode 95

What if the problem isn’t the sky, but our expectations?

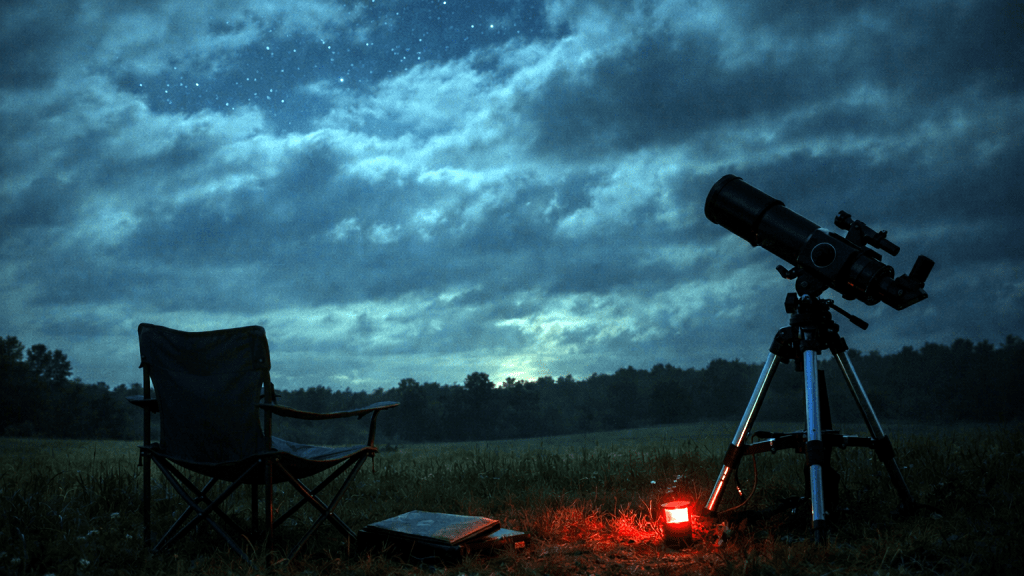

In this episode we step back from targets, charts, and techniques to talk about something every stargazer eventually encounters: the myth of the perfect night. Clear horizons, steady seeing, and flawless gear. Astronomy culture often presents these moments as normal, when in reality they’re exceptions. Most nights are compromised, interrupted, or quietly frustrating. It’s the nature of the hobby.

We explore how social media and memory itself smooth over disappointment, how unmet expectations can drain motivation, and why so many astronomers quietly drift away without realizing nothing is actually “wrong.” From dew-soaked star parties and missed comets to long stretches of waiting and adjusting, this episode hopes to show those imperfect nights still matter.

If you’ve ever packed up early, felt discouraged, or wondered whether the struggle was worth it, this one’s for you.

In the second half of the show, we’ll turn our attention back to this week’s night sky, and check in on recent solar activity that lit up the skies with auroras last week. If you caught the aurora, or tried to and came up empty, I’d love to hear your story. Photos, sightings, and near-misses are all welcome at the show website.

Transcript

Howdy stargazers and welcome to this episode of Star Trails. My name is Drew and I’ll be your guide to the night sky for the week of January 25 through the 31st.

This week we take a break from science to ground ourselves in the reality of the night sky, and how to stay motivated when the stars aren’t cooperating. I’ll talk about frustrations when dealing with the night sky, and how to manage expectations when it comes to the myth of the perfect night sky.

Later in the show we’ll survey the celestial objects worth our attention this week, and check in with the Sun after several days of intense activity last week.

Whether you’re tuning in from the backyard or the balcony, I’m glad you’re here. So grab a comfortable spot under the night sky, and let’s get started!

This week is the final episode in our January arc of episodes aimed at brand new astronomers. We’ve covered the basics of how to begin stargazing, we took a deep dive into one of the monster constellations of the winter, Orion, and just last week, we covered how the sky moves, how planets wander, how stars rise and set, and how nothing above us is ever truly still.

In this episode, we’re going to dial back the astronomy, and maybe get a little meta. This isn’t about seeing particular objects or how to observe a nebula. It’s not about how the sky behaves, but rather how we behave under it.

Astronomy, especially the kind practiced by amateurs like us, has a quiet, unspoken problem. And this problem is one that often causes frustration and in some cases, keeps us indoors on nights when we could be observing. The idea I’m circling is the myth of the perfect night.

You know the one: Clear skies from horizon to horizon. Steady air. Everything visible exactly when you want it to be. The telescope works flawlessly. Your charts make sense. Your patience holds.

It’s the night we imagine when we’re stuck at work, watching clouds roll by on a weather app. It’s the night social media seems to promise is just one dark site away.

And it’s the night many of us quietly measure ourselves against.

The problem is, almost no real night ever looks like that. And if we’re not careful, that expectation can quietly drain the joy out of this whole thing.

There’s a kind of lie baked into how astronomy is often presented, not an intentional lie, but rather a lie by omission.

Looking at images of space online, especially those taken by fellow amateurs can be awe-inspiring. We see the results. We see the images. We see the moments where everything worked, when a dozen hours of integration in a light-polluted sky somehow produced the most gorgeous image of Andromeda you’ve ever seen.

What we don’t see is the waiting. The clouds that showed up at dusk and never quite left. The bad seeing that turned Jupiter into a boiling mess. The targets that were technically “up,” but practically unreachable.

Nobody posts the night they spent mostly checking their telescope’s collimation and wondering if the haze was getting worse. Nobody posts the hour they waited for the sky to settle, only to pack up tired and cold.

Not because those nights are shameful, but because they don’t photograph well. They don’t make for good stories, or social media fodder.

And yet those nights are the rule, not the exception. Let’s be real: Most observing sessions are compromised in some way. The atmosphere rarely cooperates. Light pollution always finds a way back in. Fatigue sets limits. And astronomy happens in the margins of imperfection.

There’s another trick at work here, and it’s a very human one: Memory edits.

Speaking from personal experience, I can recall nights at the dark site where it felt like the glowing gas of the Milky Way was just hundreds of feet above us, and so bright that it already looked like a long exposure. Or the time when you gazed at Jupiter or Saturn and it felt like you were on a spaceship on a close approach.

I’m not making this up — these are my own memories, and while I know they are somewhat false, they are in my mind’s eye, representing some of the best nights of observing I’ve ever experienced.

Over time, our minds smooth the rough edges off past observing sessions. We remember that we saw Saturn, but not the frustration beforehand. We remember that meteor shower, but not the clouds that wiped out half the night.

The past becomes cleaner than it ever really was. And then the present feels broken by comparison. A newcomer looks up, struggles, misses something, and thinks, “I must be doing this wrong.”

An experienced observer has an off night and wonders what’s changed, even when nothing has.

This is what it has always been like. Here’s the uncomfortable truth that no one really advertises: Astronomy does not reward effort on demand.

You can do everything “right” and still come away with very little to show for it. And if your expectation is that effort guarantees payoff, astronomy will eventually feel cruel.

I love star parties, and I try to attend all the ones put on by my local club. I’ve had amazing nights with perfect seeing, the darkest skies imaginable. So dark that it felt like I was walking around in a three-dimensional star field.

But the last three times I’ve attended its been fairly rotten in regards to seeing. Humidity in the air collects as dew on scopes and turns black skies into a grey washout. Low-lying clouds drift in and wreck the one shot at seeing the hot comet everyone has been chasing, and yes, sometimes it just rains. Sometimes we arrive early, set up scopes, wait for hours, and tear them back down 30 minutes after dusk because the conditions aren’t working.

If this sounds like Sisyphus pushing a rock up a hill, you’re not wrong. Some people eventually drift away from the hobby because of frustration. That’s the myth of the perfect night—and it does more damage than clouds ever could.

So if that night doesn’t really exist. if most sessions are compromised, if frustration and waiting are built into the experience, then what are astronomers actually doing all night?

If you’re picturing nonstop discovery, object after object, revelation after revelation, I want to gently reset that image. Most of the night is spent waiting.

Waiting for darkness to fully arrive, waiting for optics to cool, waiting to see if the atmosphere settles down, and waiting to find out whether the forecast was lying to you.

This isn’t a failure state, it’s the default.

And that can be disorienting, especially when you’re new. It doesn’t feel productive. Nothing dramatic is happening. The sky isn’t putting on a show yet—or maybe it never will. More doubt sets in: When will I ever get to use that new telescope I spent several thousand on. Or, and this applies to me, why can’t I ever get a clear night to shoot some astrophotos worth posting?

But this waiting is part of the work. It’s how you learn the rhythm of a night. How you notice subtle changes. Remember, the sky is a living system with moods.

Then there’s adjusting. Adjusting focus. Adjusting balance. Adjusting expectations.

Something is always slightly off. The finder isn’t quite aligned. The eyepiece that worked beautifully last week suddenly feels wrong. The red light is too bright. The red light is too dim. The gloves are too thick. The chair is never at the right height. My knees are taking abuse from trying to dial in the right view on my camera, and why the hell can’t I get these stars in tack-sharp focus?

Astronomy is an endless series of small corrections. Like anything else, it requires practice, preparation, and a deep insight into the workings of your gear. And there will always be problems.

You’re learning how to work with imperfect tools under imperfect conditions. You’re learning how much precision is “good enough.” You’re learning when to stop chasing perfection and start observing what’s actually there.

A lot of the night is also spent trying and failing and trying again. You hunt for something faint. You think you see it. Then you lose it. Then you wonder if it was ever there at all.

This is how visual astronomy works. The line between seeing and not seeing is often thin, and your brain is part of the instrument. Learning to trust it, while also questioning it, is a strange, quiet discipline.

Maybe you saw a faint galaxy or nebula. Maybe you didn’t. And yet that still counts. A bad day doing astronomy has to be better than a good day at work right?

There’s also repetition, which rarely gets talked about. You observe the same objects again and again, not because you forgot them, but because each visit teaches you something new. The sky changes. Your experience changes. Your eye changes. You’ll develop favorites, just like I mentioned in a past episode how I always “check in” on my favorites, Orion, the Pleiades and Andromeda.

Progress in astronomy doesn’t usually look like novelty. It looks like familiarity. It looks like knowing exactly where something should be, even if you never quite get the view you hoped for that night.

And yes, sometimes there’s boredom.

Long stretches where nothing dramatic happens. Where you’re cold. Or tired. Or distracted. This is where a lot of people assume they’re doing something wrong.

Boredom is just curiosity without payoff yet. It’s the cost of staying present when the universe isn’t offering instant reward. Astronomers learn that attention itself is the practice.

And this brings me back to star parties.

From the outside, they look ideal: dark skies, great company, rows of telescopes pointed upward. But anyone who’s actually been to a few knows the truth.

There are logistics. There’s exhaustion. There are nights where the sky doesn’t cooperate at all. There are evenings where you spend more time talking than observing. And that’s not a failure of the event.

Some of my favorite nights at a star party had very little to do with space at all. Sometimes it’s smoking cigars and drinking bourbon with more experienced observers and trying to absorb all the information you can from them. Sometimes it’s picking up a guitar and strumming chords over a folk tune while the heady aroma of grilled meat wafts between the observatories.

That’s the reality of bringing humans, equipment, and weather together in one place and hoping for the best.

Some of the most meaningful nights aren’t the ones where you saw the most, they’re the ones where you learned something, shared a frustration, or simply stayed out longer than you thought you would.

Most astronomers aren’t chasing spectacle all night. They’re building a relationship with the sky in their own personal way. For me, that means grabbing my camera and tripod and wading into waist deep foliage in a farm field to shoot the Milky Way, while quietly meditating on my place in the universe. For others, that’s setting up a smart scope, sharing binoculars with a neighbor, or trading whiskey recommendations amid talk of T. Coronae Borealis.

This is the reality of our hobby. Waiting. Adjusting. Failing. Trying again. Boredom mixed with curiosity.

The goal was never the perfect night. The goal was learning how to keep showing up.

Here’s the quiet shift that happens once you let go of the perfect night. A “bad” night of astronomy starts to look very different.

Astronomy was never really about extraction. It isn’t about pulling something out of the sky and taking it home with you. It’s about showing up, paying attention, and learning how to be present with something that doesn’t respond to pressure.

Even a night where you packed up early still reminded you why you came out in the first place. An evening where nothing worked still deepened your understanding of how fragile those perfect moments really are.

There’s a temptation to think of astronomy as a transaction. I give the sky my time and effort and in return, it gives me wonder.

But the sky doesn’t work that way. Sometimes it gives you a breathtaking view. Sometimes it gives you frustration. And sometimes it gives you nothing at all.

And yet, we keep going back, because occasionally, we do have a rewarding experience. You’re not doing astronomy “wrong.” This is how the hobby works. If you need immediate gratification, maybe visit a planetarium.

Astronomers keep coming back out under compromised skies. Not for perfection, or productivity, or for content. But because there’s value in returning to something that doesn’t bend itself to your schedule. Because there’s meaning in attention, even when the universe is indifferent.

After a quick break we’ll be back to go over what you can expect to see in the night sky this week. Stay with us.

Welcome back.

We begin this period with a First Quarter Moon late tonight, meaning about half the lunar disk is illuminated and rising. Until the 31st the Moon will wax toward gibbous, brightening each night and dominating the later evening sky. A waxing gibbous Moon can interfere with deep-sky observing, but it’s excellent for lunar surface detail and Earthshine around sunset.

Jupiter will be prominent throughout this week, still glowing brightly after its recent opposition earlier in January and visible all night. It sits in Gemini, near the bright stars Castor and Pollux. Saturn will be an evening planet after sunset, fading toward late evening as the week progresses.

Uranus and Neptune remain in the evening sky in late January but require binoculars or a small telescope to pick out. Be sure to check in with an app like Stellarium for the exact locations. Mercury, Venus, and Mars are too close to the Sun’s glare during this period to be practical targets from most latitudes.

Some notable deep sky objects are up during this period. Cruise through Gemini for lesser-observed open clusters like NGC 2158, a compact but interesting cluster that’s about 2 billion years old. It’s located immediately southwest of another low-key target, Messier 35, also known as the “Shoe-Buckle Cluster.”

Lepus the Hare, just south of Orion, is subtle to the eye but contains a few faint stars and can serve as a gateway to the faint galaxy NGC 1964 on dark nights. If you can pull it out of the darkness, NGC 1964 is a lovely barred spiral galaxy about 65 million light years away.

Eridanus, the celestial river stretching from Orion toward the south, hosts scattered galaxy fields such as NGC 1533 and other magnitude 10–11 galaxies that reward patient binocular or small-telescope sweeps. MGC 1533 is a lenticular galaxy about 62 million light years away, and resembles an oval blob with a bright core.

By the way, when we refer to an object as Messier 33 or NGC 2158, we’re referring to their cataloged names. NCG means “New General Catalog” and Messier objects are named for the French astronomer Charles Messier, who cataloged 110 objects in the 18th century.

Even though major meteor showers like the Quadrantids peaked a few weeks earlier, observing sporadic meteors and satellites remains rewarding under dark skies, particularly earlier in the evening before the Moon rises. Use a nice pair of binoculars after dusk and scan around the sky. With some patience, you’re almost certain to see dozens of Starlink satellites zipping around.

Space enthusiasts can point their star charts toward Ophiuchus before dawn to locate the rough region of Voyager 1, a fun conceptual target even though it’s impossible to see with optical equipment. It’s just nice knowing it’s out there.

The Sun turned the dial up to 11 last week, producing one of the most energetic space-weather events in years. On January 18 and 19, a very strong X-class solar eruption sent a fast-moving cloud of magnetized plasma straight toward Earth. When that coronal mass ejection slammed into our planet’s magnetic field on the 19th, it stirred up a severe geomagnetic storm, officially rated G4, meaning the disturbance was intense enough to seriously shake Earth’s magnetic environment.

Under the right conditions, storms like this can drive auroras well outside the usual high-latitude zones. Indeed, reports and photos from around the Northern Hemisphere showed the aurora borealis lighting up skies farther south than usual on the night of the storm. Observers in parts of Europe, the U.S. Southwest, and even mid-latitude regions shared images of unusual auroral activity, even though it didn’t quite reach as far south as some forecasts had hoped.

Part of the reason the aurora displays were “hit-or-miss” for more southerly viewers comes down to magnetic geometry. Even though the storm was strong overall, the exact orientation of the incoming magnetic fields didn’t always line up in a way that let the energy pour into Earth’s upper atmosphere everywhere. That meant the auroras ended up being very bright where conditions were favorable, but more confined than some early predictions suggested.

Solar physicists are calling this one of the most significant space-weather events in the last couple of decades because there was an associated solar radiation storm, a prolonged high-energy particle flood, that hasn’t been seen at this scale in more than twenty years.

If you spotted or photographed any aurora, I’d love to hear about it. Drop me a line over at the show website or ping me on Bluesky.

That’s going to do it for this week. If you found this episode interesting, please share it with a friend who might enjoy it. The easiest way to do that is by sending folks to our website, startrails.show. And if you want to support the show, use the link on the site to buy me a coffee. It really helps!

Be sure to follow Star Trails on Bluesky and YouTube — links are in the show notes. Until we meet again beneath the stars … clear skies everyone!

Support the Show

Connect with us on Bluesky @startrails.bsky.social

If you’re enjoying the show, consider sharing it with a friend! Want to help? Buy us a coffee! Also, check out music made for Star Trails on our Bandcamp page!

Podcasting is better with RSS.com! If you’re planning to start your own podcast, use our RSS.com affiliate link for a discount, and to help support Star Trails.

Leave a comment