What Stars Do While They’re Alive – Star Trails: A Weekly Astronomy Podcast

Episode 97

Stars are easy to take for granted. They rise, they set, and they seem unchanged from one night to the next. But in this episode of Star Trails, we shift our focus to what stars are actually doing right now, shaping nebulae, building solar systems, regulating star formation, and quietly organizing the structure of galaxies around them.

We explore stellar nurseries like the Orion and Eagle Nebulae, where young stars actively sculpt their birth clouds, and look at star clusters, both open and globular, as living communities that reveal how mass determines a star’s fate. Along the way, we unpack one of the strangest facts in astronomy: that the smallest, coolest stars may live for trillions of years, far longer than the universe has existed so far, and how we know that’s true.

Later in the show, we step outside and survey the night sky for February 8–14, demystifying the so-called “planetary parade” by using it as a guide to the ecliptic — the shared path planets follow across the sky.

Transcript

Howdy stargazers and welcome to this episode of Star Trails. My name is Drew and I’ll be your guide to the night sky for the week of February the 8th to the 14th.

This week we continue our exploration of the lives of stars, in particular, the ones alive right now that are shaping the solar systems, nebula and even galaxies that surround them. We’ll talk about how they are born, and how they live their lives.

Later in the show we’ll take a look at this week’s sky, and I’ll demystify the phenomenon of the so-called planetary parade. One of those is forming right now, and it could make for some interesting views.

Whether you’re tuning in from the backyard or the balcony, I’m glad you’re here. So grab a comfortable spot under the night sky, and let’s get started!

When we look up at the night sky, it’s easy to think of stars as static—fixed points of light that simply exist, unchanged, night after night.

But stars are anything but passive.

While they’re alive—right now—stars are shaping their surroundings, organizing matter, and quietly steering the future of the universe. They are not just objects in space. They are active agents within it.

Stars also don’t exist in isolation. That sense of solitude is mostly an illusion created by distance. Most stars are born inside enormous clouds of cold gas and dust drifting through galaxies. These clouds are often called stellar nurseries, and while that name emphasizes beginnings, what matters for tonight is what happens after stars appear.

Once stars form, they don’t politely step aside and let the nursery continue undisturbed. They interfere.

A stellar nursery becomes an active construction site the moment stars turn on. Young stars pour out radiation and stellar winds. Their light heats nearby gas, their pressure pushes material away, cavities open up inside the cloud, dense regions are eroded, and other regions are compressed. In some places, star formation is shut down entirely as gas is dispersed. In others, new stars are triggered as material is squeezed just enough to collapse.

Stars don’t just come from their environments. They immediately begin reshaping them.

A nearby and famous example of this process is the Orion Nebula. When you look at Orion through a telescope, you’re not seeing something ancient or finished. You’re seeing an ongoing process. Massive young stars flood their surroundings with intense ultraviolet light, sculpting glowing walls of gas and carving dark lanes where dust blocks the light. Some regions are being cleared out, while others are actively forming new stars. Orion is not a snapshot of the past—it’s stellar influence unfolding in real time.

Another striking example is the Eagle Nebula, home to the famous Pillars of Creation. Those towering columns of gas are not quietly building stars in isolation. They are being actively eroded by radiation from nearby massive stars. The pillars themselves are temporary structures, slowly being destroyed by the very environment that surrounds them. This is what stellar influence looks like: creation and destruction unfolding together over millions of years.

Stars also rarely form alone. Most are born in groups called star clusters, and these clusters come in two very different flavors.

Open clusters are loose, relatively young groups of stars that form together inside stellar nurseries. Their gravity is weak, and over time the stars drift apart, spreading into the galaxy. These clusters let us watch stellar evolution in its early and middle stages.

A beautiful example is the Pleiades, visible to the naked eye as a small dipper-shaped group of stars. It’s a young cluster, still interacting with leftover dust from its birth cloud. Another is the Hyades, an older, more spread-out cluster that shows what happens as gravity slowly loses its grip and a stellar family dissolves.

Open clusters remind us that many of the stars we see—including our own Sun—likely began life with siblings that are now scattered across the Milky Way.

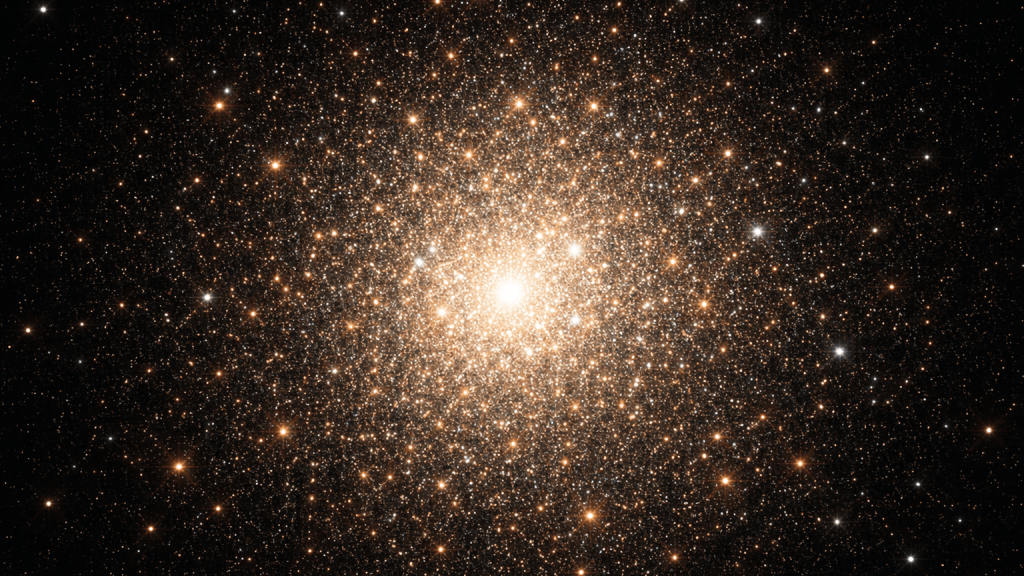

Globular clusters, on the other hand, are something else entirely.

These are dense, ancient spheres containing hundreds of thousands of stars, all bound tightly by gravity. They formed early in the galaxy’s history and have remained intact for billions of years. Inside them, stars are packed so closely that stellar interactions are common, and the environment is far more crowded than anything near our Sun.

One of the finest examples visible from the Northern Hemisphere is the Hercules Cluster. Through binoculars or a telescope, it appears as a dense, glowing ball of stars—an entire ancient stellar city suspended in space.

Globular clusters show us what happens when stars live their lives together for immense spans of time. They are reminders that stellar evolution is often a communal process, not a solitary one.

Clusters also reveal something fundamental about stars.

When all stars in a cluster form at the same time, the differences we see between them are not about age. They’re about mass.

Mass determines how a star behaves while it’s alive. Massive stars burn hot and fast, with fusion running furiously in their cores. They shine brilliantly but briefly, sometimes for only a few million years. Smaller stars are different. Red dwarfs—the smallest stars capable of sustaining fusion—burn their fuel slowly and efficiently. They mix their hydrogen throughout their interiors, wasting very little, and as a result, they endure.

Based on how slowly red dwarfs consume their fuel, astronomers calculate lifespans not in billions of years, but in trillions. Ten trillion years, possibly more. The universe itself is only about 13.8 billion years old, so how can we possibly know that some stars will live for trillions of years when the universe hasn’t been around nearly that long?

The answer is that astronomy doesn’t rely on waiting. It relies on physics. We understand how stars work at a fundamental level: how much fuel they contain, how fast they burn it, and how efficiently that energy is produced. Once you know those things, you don’t need to watch the entire lifespan play out any more than you need to wait for a candle to burn out to estimate how long it will last.

There’s also an important piece of observational evidence. Not a single red dwarf has ever been observed to die of old age. We see young red dwarfs, old ones, and ancient ones—but no red-dwarf remnants created through normal stellar aging. The universe simply hasn’t been around long enough for that to happen. That absence isn’t a mystery. It’s a confirmation.

While stars are alive, they are also busy building systems. When a star forms, it is surrounded by a rotating disk of gas and dust. Inside that disk, material collides and sticks together, eventually forming planets. Stars don’t just host planets—they define the architecture of entire solar systems. A star’s gravity sets orbital paths, its radiation shapes atmospheres, and its early activity determines which planets survive and which never fully form.

Stars also define where life might exist. A star’s brightness determines where liquid water could persist on a planet’s surface, but that zone is not fixed. As stars age, they slowly brighten, and the habitable zone moves outward. Planets drift into and out of favorable conditions not because they move, but because their star evolves.

Beyond planets, stars provide something even more fundamental: persistent energy. Not just light, but long-lasting energy gradients that keep chemistry active, atmospheres dynamic, and complexity from running down too quickly. Stars act as long-burning engines that hold complexity open—locally and temporarily, but long enough to matter.

Zoom out even further, and stars help define the structure of entire galaxies. They trace spiral arms, outline galactic disks, and mark where gas collects and where it doesn’t. Galaxies don’t look the way they do despite stars. They look that way because of them.

This leads to a quiet realization beneath all of this.

We are living in a very particular chapter of cosmic history. Star formation is still active. Bright, Sun-like stars are common. Heavy elements are abundant. Planetary systems are widespread. In the far future, the universe will belong to small, dim, long-lived stars, glowing faintly for trillions of years while galaxies slowly fade.

Right now is a relatively bright chapter. Stars are still alive in large numbers, still energetic, still shaping their environments.

They are still doing their work.

Stars are not static points of light. They heat gas, sculpt nebulae, regulate star formation, build solar systems, and define where complexity can exist. They don’t simply shine.

They organize matter, patiently, collectively, and over immense spans of time.

And all of that is happening right now.

After a quick break we’ll check in with what you can see in the night sky this week. Stay with us.

Welcome back.

This week the Moon is moving through its waning gibbous phase, having passed third quarter on February 9. As the week goes on, the Moon rises later each night, which means darker skies earlier in the evening. By mid-week, you’ll have a more generous window for observing before moonlight becomes an issue, especially if you’re heading out shortly after sunset.

You may hear this week described in headlines as a “parade of planets,” and rather than dismissing that outright, it’s actually a good opportunity to explain what’s really going on — and why planets so often appear in the same part of the sky.

All of the major planets in our solar system orbit the Sun in nearly the same flat plane. From Earth, that plane projects onto the sky as a gentle arc called the ecliptic. It’s the same path the Sun appears to follow across the sky over the course of a year, and it’s also where the Moon and planets spend almost all of their time.

So when several planets are visible at once, they aren’t lining up by coincidence. They’re simply tracing the same shared highway across the sky.

This week, that highway runs low across the western and southwestern sky after sunset. Jupiter is the easiest place to start, bright, steady, and well above the horizon as twilight fades. Saturn sits much lower, closer to the horizon, and requires a bit more patience as it lingers in the glow of sunset. Mercury makes only a brief appearance very low in the west, rewarding observers who look early and know where to scan.

That’s why planetary “parades” tend to be quieter than the headlines suggest. The planets aren’t stacked in a dramatic row, and they won’t leap out at you unless you already understand the layout of the sky. What you’re really seeing is the ecliptic itself, the architecture of the solar system made visible.

If you step outside and slowly trace that gentle line across the sky, from west toward south and then east, you’re following the same plane planets have orbited in for billions of years. Once you recognize it, you’ll start seeing it everywhere: in where planets rise, where the Moon travels, and even where eclipses become possible.

Once twilight fades, this week is a great time to explore some quieter corners of the winter sky — objects that don’t always get top billing but reward a little patience.

In Gemini, look for the open cluster Messier 35. It’s a rich, wide cluster that works beautifully in binoculars and small telescopes. It has a loose, scattered character that feels very different from tighter, more famous clusters.

Lower in the southern sky, in Puppis, you’ll find a trio of often-overlooked open clusters: Messier 46, Messier 47, and Messier 93. These three make a nice study in contrast — one dense and rich, another looser and brighter, and one smaller and more compact. They’re excellent targets for small telescopes once they’ve climbed clear of the horizon.

For a globular cluster that tends to fly under the radar, look just below Orion toward the constellation Lepus for Messier 79. It appears as a tight, concentrated glow through modest telescopes and offers a very different feel from the more famous globulars that dominate summer skies.

Observers with darker skies may want to spend some time in Monoceros, the faint constellation between Orion and Gemini. Here you’ll find NGC 2264, sometimes called the Christmas Tree Cluster. It’s a subtle region combining a scattered group of young stars with faint surrounding nebulosity. This is not an object that jumps out immediately — it rewards lingering, careful looking, and wide-field views.

This is a good week to think of stargazing as wandering rather than checking boxes.

Let the Moon rise later. Trace the ecliptic across the sky, and spend time with objects that don’t demand attention.

That’s going to do it for this week. If you found this episode interesting, please share it with a friend who might enjoy it. The easiest way to do that is by sending folks to our website, startrails.show. And if you want to support the show, use the link on the site to buy me a coffee. It really helps!

Be sure to follow Star Trails on Bluesky and YouTube — links are in the show notes. Until we meet again beneath the stars … clear skies everyone!

Support the Show

Connect with us on Bluesky @startrails.bsky.social

If you’re enjoying the show, consider sharing it with a friend! Want to help? Buy us a coffee! Also, check out music made for Star Trails on our Bandcamp page!

Podcasting is better with RSS.com! If you’re planning to start your own podcast, use our RSS.com affiliate link for a discount, and to help support Star Trails.

Leave a comment