How Stars Die (Including the One That Keeps Us Alive) – Star Trails: A Weekly Astronomy Podcast

Episode 99

In this episode, we wrap up our month-long series on stars by exploring their final acts.

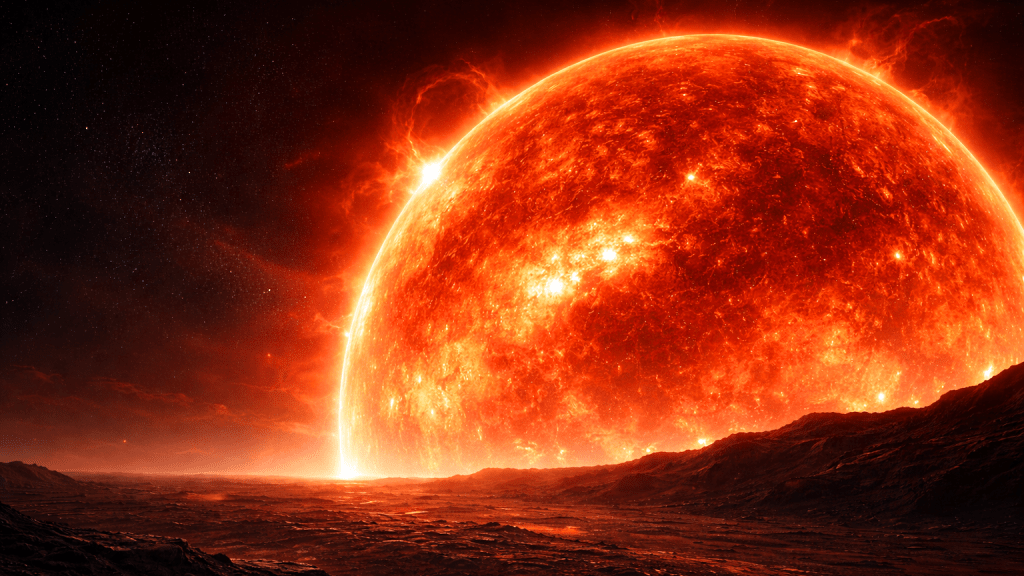

Most stars don’t explode. They grow old. We’ll follow the Sun’s future as it swells into a red giant, sheds its outer layers, and becomes a dense white dwarf held up not by heat, but by quantum mechanics itself. Along the way, we’ll examine planetary nebulae like the Ring Nebula and the Dumbbell Nebula, and look at real red giants such as Betelgeuse and Aldebaran that foreshadow stellar endings.

Then we turn to the massive stars, the ones that collapse, detonate as supernovae, leave behind neutron stars and magnetars, or cross the final threshold into black holes. We’ll discuss how gravity overwhelms every known force, how black holes are categorized by size, and why even these seemingly eternal objects slowly evaporate over unimaginable timescales.

In the night sky report, we cover the waxing Moon, a six-planet evening “parade,” Jupiter shining high after sunset, and a beautiful lunar encounter with the Pleiades.

Transcript

Howdy stargazers and welcome to this episode of Star Trails. My name is Drew and I’ll be your guide to the night sky for the week of February 22nd to the 28th.

This week we wrap up our month-long series on stars by exploring how they end their lives. For some it’s a quiet process, like embers cooling after a camp fire. Others explode, and some turn into black holes, destined to live the remainder of their lives like cosmic vampires facing eternity.

Later in the show we’ll take a look at what you can see in the night sky this week.

Whether you’re tuning in from the backyard or the balcony, I’m glad you’re here. So grab a comfortable spot under the night sky, and let’s get started!

When I was a kid, I distinctly remember the night when I learned our Sun was at some point, going to die. And to be honest, it wasn’t a great feeling. Sitting on the floor in the den of my grandmother’s house, as twilight fell, I opened up my favorite astronomy tome, The Universe, by National Geographic, and read a surprisingly long and detailed account of how in some 5 billion years, our Sun would grow hotter, all life on Earth would be vaporized, and the sun would expand into a red giant, enveloping Mercury, Venus and Earth.

This was terrifying. It was the first realization that the Sun and Earth weren’t permanent. Sure, I knew I wouldn’t be around in 5 billion years to see the Sun collapse, but even as a 7-8 year old child, knowing the end was approaching like a timer counting down, created a sense of existential dread and anxiety.

Tonight, we’re wrapping up our month-long theme about stars. We’ve talked about how they form, what they are, and what they do during their epic lifespans. We’ve done some statistical analysis related to star formation and what they leave behind. But now, it’s time to talk about how stars die, including the one that keeps us alive.

The first thing to remember is most stars don’t explode. Our imagination is filled with supernovae. Stellar death is often portrayed as violent and spectacular. But the vast majority of stars don’t end that way.

As we’ve mentioned a few times this month, most stars in the universe are small red dwarfs that burn their hydrogen so slowly they will outlive the current age of the cosmos by orders of magnitude. They won’t explode; they’ll simply fade away.

Larger stars like our Sun live for about 10 billion years in what astronomers call the main sequence phase. During this time, hydrogen fuses into helium in the core. Fusion releases energy. That energy produces outward pressure. Gravity pulls inward, and the two forces balance one another in what is called hydrostatic equilibrium.

For billions of years, the Sun has existed in that quiet stalemate. But hydrogen in the core isn’t infinite. And this is where the story becomes more subtle than most of us expect. Counter to what we might expect as a star dies, some, like our Sun, actually grow in size.

When hydrogen in the Sun’s core is mostly depleted, fusion in the very center begins to slow. The outward pressure weakens. Gravity, which never takes a day off, begins to win. The core starts to contract.

And here’s the key piece: when gas is compressed, it heats up. Gravitational potential energy is converted into thermal energy as the core shrinks.

Think about how a diesel engine works. Unlike a normal gas engine, which uses spark plugs to touch off combustion, a diesel engine compresses the air in a piston to ignite fuel. Now imagine that process happening with half the mass of a star. It’s not just a small contained explosion; it’s nuclear fusion.

As the core contracts, it becomes hotter and denser. Fusion in the center has largely ceased, but the rising temperature ignites hydrogen in a shell surrounding the inert helium core. Instead of fusion happening at the center, it now happens in a thin, intense layer around it.

And that shell fusion is more energetic than the Sun’s original core fusion was.

The increased energy output pushes outward on the star’s outer layers. Those layers respond by expanding dramatically. The Sun will swell to perhaps a hundred times its current diameter, engulfing the inner planets.

Paradoxically, gravity causes the expansion. Gravity compresses the core. Compression increases temperature. Higher temperature ignites shell fusion. Shell fusion increases energy output. The outer layers expand.

As the Sun expands, its surface temperature drops. A larger surface area radiates energy more efficiently, so the outer layers cool to around 3,000 to 4,000 Kelvin. The Sun will appear redder and dimmer per unit area, even though its total luminosity increases.

This is the red giant phase.

You can look up at the night sky right now and see some famous red giants. Betelgeuse in Orion is the classic example. It’s already in its death throes, hundreds of times larger than the Sun. If placed at the center of our solar system, it would extend past Mars — possibly even toward Jupiter depending on how you measure its fuzzy outer atmosphere.

This star will not become a white dwarf. It will explode as a supernova within the next hundred thousand years or so — astronomically soon, though not calendar soon.

Aldebaran is closer to the Sun’s eventual fate. It’s a red giant, not massive enough to explode, but expanded and cooling. This is a preview of what our Sun will look like in about five billion years. It’s steady. It’s not violent. It’s simply old.

Eventually in our Sun, the contracting helium core will become hot enough — about 100 million Kelvin — to ignite helium fusion into carbon and oxygen. This ignition happens in what astronomers call the helium flash, a rapid internal event that barely disturbs the outer star. After a brief period of renewed stability, fusion once again shifts outward into shells, and the outer layers grow increasingly unstable.

Finally, the Sun will shed those layers entirely, creating a glowing planetary nebula — a delicate shell of gas expanding into space, and at the center remains the exposed core. This is where the physics turns truly strange.

What remains after the Sun sheds its outer layers is a white dwarf, roughly Earth-sized, containing about half the Sun’s current mass. It no longer generates energy through fusion. It shines because it’s hot, not because it is burning.

The density inside a white dwarf is extraordinary. A teaspoon of its material would weigh several tons. At this stage, the matter is packed so tightly that classical physics alone cannot explain what holds it up. The answer lies in quantum mechanics.

Electrons obey a rule known as the Pauli exclusion principle, which states no two electrons can occupy the same quantum state simultaneously. When gravity attempts to compress the white dwarf further, electrons are forced into higher energy states simply because there are no lower ones available. This creates a pressure, electron degeneracy pressure, that doesn’t depend on temperature.

The white dwarf isn’t supported by heat. It is supported by the structure of quantum reality itself. Afterwards, it will simply cool over trillions of years, fading gradually into darkness.

There are planetary nebula you can see right now that represent what the Sun’s far future could look like. The Ring Nebula, M57, is the exposed outer layers of a Sun-like star that died thousands of years ago. At its center is a white dwarf — the compressed remnant core.

The Dumbell Nebula is larger and easier to observe in small telescopes than the Ring Nebula. It’s another Sun-like star shedding its atmosphere.

While you aren’t likely to be able to spot it, we know of another fairly close white dwarf. Sirius, the brightest star in our sky, has a tiny companion — Sirius B — a white dwarf about the size of Earth but nearly as massive as the Sun.

It’s difficult to see visually because it’s overwhelmed by the glare of Sirius A, but it’s been imaged and studied extensively by Hubble and X-ray telescopes. That tiny dot represents quantum mechanics holding up half a star.

If a star begins its life far more massive than the Sun, the ending changes dramatically.

Massive stars burn through their fuel quickly, fusing heavier and heavier elements in their cores. Hydrogen becomes helium, helium becomes carbon, carbon becomes oxygen, and so on, building an onion-like structure of nested fusion layers. This process continues until iron accumulates in the core.

But iron is a dead end, because fusing iron consumes energy instead of releasing it.

When the core becomes iron-rich, fusion can no longer support it. Gravity wins completely. The core collapses in less than a second. Electrons are crushed into protons, forming neutrons and releasing an enormous burst of neutrinos. The collapsing core rebounds, driving a supernova explosion that briefly outshines entire galaxies.

What remains depends on the core’s mass.

If the remnant core is between roughly 1-and-a-half and about 2 or 3 solar masses, collapse halts at an even more extreme stage. Electrons and protons merge into neutrons.

The result is a neutron star — typically about 20 kilometers across yet containing more mass than the Sun. Its density is so extreme that a sugar-cube-sized piece would outweigh a mountain.

Once again, quantum mechanics intervenes. Neutron degeneracy pressure — the same exclusion principle applied to neutrons — prevents further collapse. Inside, matter may exist as a superfluid, possibly containing exotic particles or even free quarks. We are still probing this frontier with gravitational wave observations and nuclear physics experiments.

Some neutron stars spin rapidly and emit beams of radiation, appearing to us as pulsars. The Crab Nebula, M1, is the remnant of a supernova observed in 1054 AD. At its center lies a neutron star — the Crab Pulsar — spinning about 30 times per second.

Other neutron stars possess magnetic fields so intense they defy comprehension.

These are magnetars: Neutron stars with extraordinarily amplified magnetic fields, trillions of times stronger than Earth’s. The leading explanation is that rapid rotation during collapse amplifies magnetic fields like a dynamo. The result is an object capable of releasing immense bursts of X-rays and gamma rays.

They are rare and violent, but still the product of stellar collapse. And that finally brings us to black holes.

If the collapsing core exceeds the mass that neutron degeneracy pressure can support, no known force can halt the implosion. Gravity overwhelms every resistance. The core continues collapsing until an event horizon forms, a boundary beyond which light cannot escape.

A black hole isn’t a cosmic vacuum cleaner. It’s a region of spacetime so curved that all future paths point inward.

At its center, classical general relativity predicts a singularity, a point of infinite density and zero volume. But infinities in physics are usually a sign that the theory has been pushed beyond its valid domain. Most physicists suspect that a future theory of quantum gravity will replace the singularity with something finite, though we don’t yet know what.

We tend to group black holes into categories based on mass.

Stellar-mass black holes form from collapsing massive stars. They typically range from about 3 to perhaps 50 times the mass of the Sun but these objects are only tens of kilometers across. That’s astonishingly compact.

Then there are intermediate-mass black holes, which likely range from hundreds to hundreds of thousands of solar masses. Evidence for these is still emerging, but gravitational wave detections and observations of dense star clusters suggest they exist.

And finally, there are supermassive black holes. Every large galaxy we’ve studied appears to host one at its center. The one in our galaxy, Sagittarius A*, has a mass of about 4 million Suns.

In the far future of the universe, after stars have burned out, after white dwarfs have cooled, after neutron stars have decayed or collapsed, black holes may be the last major structures left. This hypothetical scenario is sometimes called the Black Hole Era of the universe, and it’s so far in the future that it makes the Sun’s 5 billion remaining years look like a brief candle flicker.

At some point, even black holes sputter out. In the weird quantum fields of a black hole, some particles manage to escape. You’ve maybe heard this term before: Hawking radiation, because it was in fact theorized by physicist Steven Hawking. Over time, and I do mean a very long time, the black hole will slowly lose mass.

We’re talking time scales that are slow even by astronomical standards. We need to shift our perspective by powers of 10 for it to even make sense. For example, the evaporation of a smaller stellar mass black hole could take years on the order of 10 to the 67th power — that’s a 1 with 67 zeros behind it. A supermassive black hole may take 10 to the 100 years or more to die. By comparison, the current age of the universe in years is “only” about 10 to the 10th power.

Black holes aren’t eternal, but for all practical astrophysical purposes, they might as well be. As they lose mass, their temperature increases. Near the very end of their evaporation, they would radiate intensely and vanish in a final burst of high-energy radiation. This final phase has, of course, never been observed and remains theoretical.

This brings me back around to where we started this episode: Pondering the dread of our own Sun’s death. Our Sun feels foundational, yet it’s temporary. But its transformation lies so far in the future that it functions more as a philosophical boundary than an impending event. Humanity has existed for only a tiny fraction of the Sun’s lifespan. If the Sun were a 70-year-old human, our entire species would have appeared only a few hours ago.

When its time comes, the Sun will not rage. It will compress, ignite new layers, expand, shed, and settle into a dense white ember held together by the quantum rules that make the universe coherent at its smallest scales.

In the meantime, it’s humbling to realize that everything heavier than helium in your body was forged in stars that lived and died before ours was born. Stellar death made rocky planets possible. It made chemistry complex. And it made us.

After a quick break we’ll be back with this week’s sky report. Stay with us.

Welcome back.

This week’s sky offers a rich mix of wandering worlds and familiar lunar phases, perfect for both binocular stargazers and people simply stepping outside after dinner.

As the Sun sets, start by finding the Moon. This week its rotating into view as a thin waxing crescent early in the week. By February 24, the Moon reaches first quarter, appearing half-illuminated and hanging high in the southern sky around sunset. By week’s end, it grows into a bright waxing gibbous, rising earlier each evening and dominating the early nighttime.

This week is especially good for planets because a slow-building planetary parade is unfolding in the evening sky. Six planets, Mercury, Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, will appear along the same stretch of sky shortly after sunset. From Earth’s perspective they trace a broad arc along the ecliptic that can be seen in a single sweep with dark skies and clear horizons.

Start your evening soon after sunset by looking low toward the western horizon. There, Venus shines brightest among the inner planets, a brilliant beacon just above the horizon. Not far below it is Mercury, still a challenge because it sits low and close to the Sun’s glare, but visible if you catch it while the sky is still dusky and the horizon is clear. Saturn also lingers in this direction, a softer yellow point that will benefit from binoculars or a small telescope to cut through twilight.

Toward the east and southeast as night deepens, you’ll see Jupiter, the brightest star in the evening sky this month. It rises early and stays high well into the night, far easier to spot than Mercury, Venus, or Saturn. In a telescope, Jupiter’s cloud bands and its large moons make for stunning details if the air is steady.

The outer ice giants, Uranus and Neptune, are also part of this extended parade, located between the brighter worlds. They are too faint to see with the naked eye; binoculars or a telescope will help you tease them out against the star fields.

The best collective view of this six-planet parade builds toward February 28, when all six planets are visible in the same post-sunset window roughly 30–90 minutes after sundown. Start with the western horizon for Venus, Mercury, and Saturn, then sweep eastward to catch Jupiter higher in the sky. Uranus and Neptune will be between them, subtle but there.

Finally, even with the Moon brightening later in the week, don’t miss a couple of quieter, skywatching opportunities earlier in the period. On the evening of February 23, the Moon moves through the northern part of the Pleiades star cluster, subtly occulting stars as it passes. It makes a fine pairing for binoculars or a wide-field telescope.

Next week we’ll return to our book club, covering chapters 6 and 7 in Nightwatch. These chapters cover deep sky objects and the planets of our solar system, and like the previous chapters, make excellent companion readings for this podcast.

That’s going to do it for this week. If you found this episode interesting, please share it with a friend who might enjoy it. The easiest way to do that is by sending folks to our website, startrails.show. And if you want to support the show, use the link on the site to buy me a coffee. It really helps!

Be sure to follow Star Trails on Bluesky and YouTube — links are in the show notes. Until we meet again beneath the stars … clear skies everyone!

Support the Show

Connect with us on Bluesky @startrails.bsky.social

If you’re enjoying the show, consider sharing it with a friend! Want to help? Buy us a coffee! Also, check out music made for Star Trails on our Bandcamp page!

Podcasting is better with RSS.com! If you’re planning to start your own podcast, use our RSS.com affiliate link for a discount, and to help support Star Trails.

Leave a comment